D: is it a morass of contradictions? Is it a game or an interactive movie? Does it have merit at all today or is it nothing more than two hours of bad FMV? Isometrics takes a trip into the mindscape of Kenji Eno’s D…

Welcome to Isometrics, a distinctly more WARPed look at the literary world of video games.Now last week I got quite a bit of discussion from a couple of people (which comprises the majority of the Isometrics viewing audience), whose opinions formed quite the dichotomy; either they agreed with my retrospective of an interesting but largely forgotten gaming figure at one of the most formative years of the medium as a literary form, or they thought I was eulogising an obscure game designer of little interest or relevance (particularly to a western audience) who made what can be described as fundamentally flawed games. Eno’s stuff was intended to go against the mould(kind of), to make an impact for what it wasn’t rather than what it was, and I’m glad that kind of spirit is continued in the discussion surrounding his legacy.

Part of my intentions with Isometrics was to highlight games that aren’t necessarily the best, or the most technically impressive, but have the most interesting ideas and scope for exploration and critical analysis, and D basically epitomises that- being a game known more for its ideas than itself.

And what are these ideas you ask? These come from two different schools of thought; on one side is the metafictional themes of D and the other the internal, psychological and sensual elements. Both aspects interplay with each other a lot in a way that Eno claims is unintentional, though given the end result I’m not entirely sure. In any case, there are certain major themes that run through D, and indeed the entire Laura trilogy.

The metafictional elements begin right with the mode of game it attempts to be. D is an interactive movie game in every respect of the word. Not only is the game entirely an on-rails adventure with nigh-ubiquitous use of pre-rendered video sequences, but it is an interactive movie in the more reductive sense of the word. D was not the first game to try and claim the interactive movie term, but it was the first to actively explore what it meant, which meant that the game had a lot of rather experimental design decisions, not all of which were positive.

The first, and most prominent of these was the concept of a virtual actress, a concept that Eno did not invent himself (the root of the idea can likely be traced as far back as Osamu Tetzuka, the “godfather of anime”, and his concept of the “Star System”), but was one of the more prominent real life attempts to bring the concept to life. The idea behind it was that Laura, the lead star of D, Enemy Zero and D2, was not in fact the same character but the same “actress” of sorts inhabiting various roles that were narratively unconnected but in a way connected through her role. It’s unclear why Eno did this, whether he thought there was money to be made in leasing out popular characters or as the first of many homages to California in the Laura trilogy, but it is definitely worth noting, since it deliberately frames the player as being an actress in the midst of playing a role, in a way very tangentially similar to the much later series Assassin’s Creed.

The other major element, and probably the most major was the deliberate restrictions on the player’s actions. A player could not pause nor save the game, which emphasised the game as a complete experience that you would go through in its entirety. Add to this a two hour time limit, the average length of a feature film and you have features that attempt to shift the experience of the game towards experiencing this story in its entirety, and typically only once at a time, since failure or at least failure to get one out of the four endings you desired meant starting the game once again from the very start.

Some people may find this annoying…

The third, and probably most positive end is the focus on cinematic presentation and the way in which it managed to create the atmosphere in D. That isn’t really to say the graphics have aged well, because in reality they’ve aged about as well as gout. This was always the bugbear people had with Full Motion Video and any game that used it intensely; because of how quickly computers developed, computer graphics could look dated and antiquated surprisingly quickly, and D, with a reliance not only on full motion video but 3D rendered characters suffered particularly heavily, especially in the facial movement department. That said, the graphics were both ambitious and very good for their time. Both of these points are made all the more impressive by the fact that WARP was a small independent game company that at the time had a team of about four animators total to work on D, all of which were using rather cheap Amiga home computers.

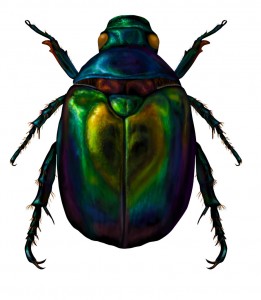

The other thing is that despite the animation limitations, there were levels of evocation that managed to shine through. An emphasis on little touches and sequences helps the animation climb very slightly up from the pit in which it graphically resides. In addition to this there is a significant influence of a wider range of films than the typical block buster, with optional scenes involving collectable psychedelic scarabs (it doesn’t make much more sense in context) that reveal that there is more to the game than mere metacommentary.

The story is at its core a psychological horror about a doctor who has lost control of his baser self and become a murderer. Laura Harris, his daughter, rushes to the hospital to try and talk him down, which is when things start to get rather more oblique. The hospital walls shift to those of a Gothic castle and Laura has two hours to try and figure out the secret of her father and the strange mental oubliette he has created for himself before they are both lost to what I can assume is madness (the game over screen doesn’t really explain much).

Now, it’s funny that the aesthetic is Gothic, because there’s a certain Gothic text that this owes rather more than a favour to…

MASSIVE SPOILER ALERT:

Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, one of the seminal texts in the first wave of Gothic horror.

In D, most of the story is left deliberately enigmatic, revealed tentatively through the finding of scarab beetles, which reveal that neither Laura nor her father Richter are who they seem, instead Richter claims they come from the same line as Dracula.

Now, given the rather… bad way that line was delivered atop the bombast, it is easy to mock the revelation as a twist there for the sake of it. Eno claims in interviews that the game was originally designed with no story and so had to have one built around it, hidden literally on shelves and in cubby holes. But at the same time, by invoking the name of Stoker’s text it indelibly makes itself an adaptation of the novel.

Perhaps, much like how the Andy Warhol produced 1974 horror film Blood for Dracula re-contextualises Dracula as a grotesque parasitic member of the old aristocracy, literally feeding on the young and innocent, here Dracula is a psychological, internal monster, one that creates a desire to feed on other people, taken to its most literal in the final scarab seen, where Laura is seen eating her mother’s arm. This, as well as the other scarab scenes were created in secret from the rest of the team and surreptitiously sneaked into the game via a rather clever disc-swapping ruse in order to fool the censors.

Consumption imagery runs rampant in the game, with the very first thing the player seems upon gaining control being a dining table, the eponymous “D’s Diner” of the mistranslated Japanese title, and the connection between food and flesh is not one the game shies away from. With bowls of blood soup, wine casks and the many scenes of mastication, there is an emphasis on the bodily, the fleshy, the fluidy, all things that 3D couldn’t really render. After these revelations comes the final, and difficult choice; kill the paternal or be killed.

There might well be a lot more( or indeed a lot less) to the game than that. Its features, for good or bad make the game one that will be debated for a good long time regarding its place in gaming history. For some it’s yet another title that tries so hard to be cinematic that it fails to be either a good film or a good game, and for others it is a very flawed and very short masterpiece.

For me, it is simply fascinating, part of gaming’s adolescent hunt for identity which comes to epitomise Eno’s western released work, as we will find out when we find Enemy Zero.

What is your take on the Interactive Movie? Did you play D and feel I missed something important? Feel free to drop a comment below, on the Geek Pride Facebook page as well as on Twitter, either through Geek Pride’s or my own Twitter page.