Introduction

With the likes of the Twilight Series, True Blood and The Vampire Diaries filling our screens, it is clear many people now associate Vampire with Edward or Bill Compton, with attractive young actors and a sexiness associated with restraint and danger.

However this was not always the case. Their thirst for blood, their undead nature and their weakness to sacred items terrified people throughout history, causing panic and many grave disturbances (pun intended!).

So how did this transformation take place?

Legends

There have been many legends of blood-sucking creatures but Vampires as we can recognize them were corpses inhabited by their vengeful spirits. Legends differed as to why these souls would return; Romany legends of the Bhuta attributed their return to an ‘untimely death’ whereas Hinduism and Romanian mythology thought that suicides and people who lived other unholy lives (such as sorcerers and those who committed grievous sins) would return.

Another common aspect was the thirst for blood, though this often manifested as the consumption of human flesh. The obvious terror this presented was the shift in the food chain; we’re used to being top of the tree, to not being the prey of something stronger and faster. Being fed upon, having to face a creature beyond your limitations, appeals to the reptilian parts of our brain; the fight or flight aspect which remembers when we were small and hunted.

There’s also the significance of blood; always related to the family, to your past and heritage, the theft of blood can be personal, an affront. In the West particularly, blood was closely linked to Paganism and Witchcraft. Especially before the eighteenth century, when witch hunts were common, the Vampire’s need to drink blood linked them with imagined evils and the devil.

Finally, they hated sacred items such as holy water and religious symbols. With religion so strong, Vampires having no power over, or even being injured by, such things meant people could not sympathize with them. Even where the legends stated that it was not the soul’s fault that they’d become Vampires, such as where they had committed suicide, the creatures were hated and feared. And the corpses of anyone suspected of being a Vampire were readily desecrated as a result.

Eighteenth Century Vampire Controversy

But Vampires were just small legends, rural beliefs of Eastern Europeans or creatures from classical mythology. It was a series of reported Vampirism cases in Eastern Europe which brought them into the mainstream. This was later dubbed the ‘Eighteenth Century Vampire Controversy’

In 1721 in Eastern Prussia and then between 1725 and 1734 in the Habsburg Monarchy, government officials were involved in cases of Vampirism, reporting on attacks and documenting the corpses of people who had either been Vampires or had been attacked by them. The case of Arnold Paole, a reported Vampire in the Serbian region in 1732, in particular was widely published and distributed across Europe, starting a generation of debate and controversy compounded with ongoing reports of Vampirism from rural Eastern Europe.

Then, as the debate began to die down, a French theologian named Dom Calmet produced two treatises on the report of Vampirism which reignited the controversy. The first of which was in 1746 and the second in 1751. These were, at the least, agnostic towards the existence of Vampires and even admitted that some corpses could have been preserved by Vampire attacks. This was in spite of Calmet’s skepticism towards the existence of Vampires, which fanned the flames of the controversy further.

It was only when Gerard van Swieten, the personal physician to the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, was sent to investigate Vampire attacks that the controversy died. His essay Discourse on the Existence of Ghosts, presented a solid case against the ‘simple’ beliefs of rural people and inspired others to examine the reports of Vampirism and find other, more mundane reasons for deaths attributed to Vampires, such as disease or contaminated water supplies.

This convinced the Empress to instigate laws against the traditional process for killing vampires, which put paid to the controversy across Europe. Reports died down and the Age of Rationality truly took hold.

But the Vampire was now in our consciousness, a superstition for writers to add flesh to. The creatures appeared for generations as vicious creatures, monsters to be feared, staying with the original legends.

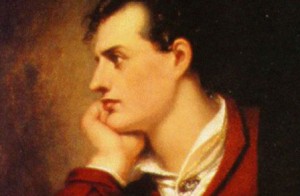

However, this changed when Lord Byron produced his epic poem The Giaour, which paved the way for the modern Vampire and the romanticizing of the creatures. Lord Byron recognized a metaphor for lust in the thirst for blood and produced a more sympathetic view of the Vampire, something more understandably human. He also added the concept of the undead passing its condition on to the living from feeding, which had not been a part of the Vampire mythos until then.

This, I believe, was the beginning of Vampires becoming the subject of fantasies; the transmission of Vampirism related to our most basic of urges, the desire to procreate, to pass our DNA on to the next generation. Vampirism became like sex, with infection being a metaphor for pregnancy, and thusly Vampires were creatures of lust.

It was also Lord Byron who inspired the first truly romantic Vampire; his physician, John Polidori, wrote the short story The Vampyre and created the Vampire character Lord Ruthven. Lord Ruthven was the first example of a Vampire being sexy and alluring, of them having refinement and restraint despite their private and abhorrent urges – a very Victorian trait, one which many could associate with. This Gothic novel gave birth to the idea of a Vampire being not just a fantastic creature but also an attractive being.

Lord Ruthven and The Vampyre became an immediate sensation, inspiring many writers to pick up this particular incarnation of the Vampire. He was adapted into several other stories and inspired at least four different plays, two operas and various poems. It was only after Bram Stoker’s Dracula became famous that Lord Ruthven faded.

Since then, the Vampire has varied between being a monster and being a fantasy. The current spate of attractive Vampires is simply a return to Polidori’s concept. Many view these works as perversions of the Vampire myth but they are merely continuing the traditions which Lord Byron started and inspired, modernizing these ideas and concepts.

Just as Byron and Polidori ended up typifying the perfect Victorian gentleman with their Vampires, we now have authors turning Vampires into the perfect modern man; they are restrained, withhold the transmission of their condition and are in control. They are what women in general want a man to be; considerate, tempered and restrained… until they want them to be otherwise.

So if you want someone to blame for sparkling Vampires and women swooning over Robert Pattinson, it’s not Stephanie Meyer; it’s Lord Byron.

I always suspected…

God dammit I knew it! 😉

Just like to add that my favourite sexy vampire is Brad Pitt’s Louis de Pointe du Lac. Yum 😀

[…] The vampires most people are familiar with (such as Dracula) are revenants — human corpses that are said to return from the grave to harm the living; these vampires have Slavic origins only a few hundred years old. But other, older, versions of the vampire were not thought to be human at all but instead supernatural, possibly demonic, entities that did not take human form. https://www.geek-pride.co.uk/when-did-vampires-become-so-sexy/ […]