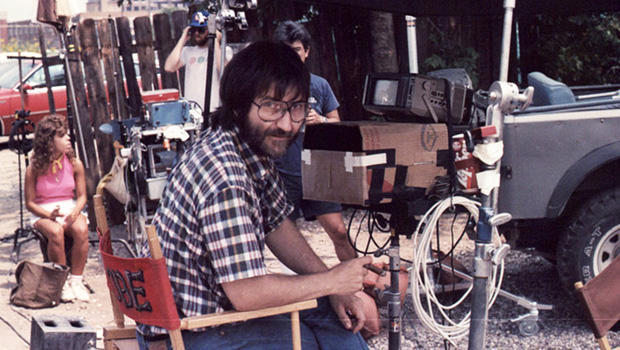

First Wes Craven, then George A. Romero, and now Tobe Hooper…having to write these types of article has unfortunately become a regular occurrence lately. Having to eulogise movie icons in 2000 words or less is a difficult task at the best of times, but when they have had such an impact on your personal movie tastes, you worry about not doing the justice that they truly deserve.

William Tobe Hooper, one of the most celebrated horror/cult movie directors of the late 20th century, passed away recently at the age of 74, due to natural causes. Many fellow directors and horror alumni have been quick to pay tribute to both the wealth of cinematic delights that Hooper left behind, as well as to the man himself.

To say that Tobe Hooper was an eclectic director would be a massive understatement. While he was be most readily remembered for his 1974 horror masterpiece The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which is recognised for kick-starting the modern ‘slasher movie’ genre – there was certainly more strings to his bow than just slashers. From the big-budget television adaption of Stephen King’s epic vampire novella Salem’s Lot, to the box-office smash supernatural family drama Poltergeist, and to the camp sci-fi brilliance of Lifeforce – Hooper covered a lot of ground extremely successfully. But if it ends up being the sadistic adventures of Leatherface and the rest of the Sawyer family that will define Hooper’s career, then that is certainly a fine legacy to have.

Born in 1943 in Austin, Texas – Hooper caught the cinema bug at an early age thanks to his cinephile parents Norman and Lois, who owned a relatively successful movie theatre in the Austin area. When he became interested in creating his own features around the age of 10, Norman was more than happy to lend both his encouragement and his equipment to aid his son’s experimentation. This subsequently led to college years studying Film/Television, and to a fledgling career as a documentary cameraman

After Hooper’s first attempt at an original non-documentary feature – the low-budget drama/ode to the late 60’s ‘Hippy’ culture, Eggshells (1969) – failed to gain any traction in the independent cinema scene, Hooper decided to make a horror project heavily influenced by the story of Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, that would explore the theme of murder in the isolation of the rural US South – that project became Texas Chainsaw.

Rightly heralded as one of the most visceral experiences in cinema history, it tells the story of a group of teenage friends driving across Texas, who make an unfortunate detour and fall foul of a family of murderous red-neck cannibals. There is an inherent feeling of dread that permeates throughout the movie – right from the gang’s initial interaction with the crazed ‘hitch-hiker’ character, the exploration of the Sawyer family home and its grisly furnishings, and of course the mental torturing of protagonist Sally around the dinner table – the tension does not drop an inch, which makes for an uncomfortable watch even after all these years.

It’s hard to quantify what makes the original Chainsaw so iconic. Although it wasn’t the original ‘slasher’ movie (that distinction would probably fall to either Michael Powell’s subversive Peeping Tom, or even Hitchcock’s Psycho), but it was certainly the movie that went on to inspire what became known as the ‘Golden Era’ of the slasher (1974-1984) – with movies such as Black Christmas (1974), Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), and A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984) following in its horrific wake.

It’s a movie that most people will automatically have an opinion about, even before having seen it – the most nihilistic of movie titles giving the movie an almost unrivalled grisly reputation. It suggests a film which should be drenched in gore, but which surprisingly contains next to none – the infamous ‘meat-hook’ scene for example is definitely graphic in its portrayal, but the tearing of flesh is never actually shown.

But it was the power of this reputation that led the film to fall victim to the moral panic that existed around horror cinema during the late 70s/early 80s, particularly in the UK and in parts of Europe. Firstly it was denied widespread cinema release in various European territories, and then was caught up in the ‘Video Nasties’ hysteria – which saw the widespread censorship/outright banning of any movie deemed ‘unacceptable’ by a panel of so-called experts (the almost puritanical BBFC/the mainstream press/and right-wing religious groups), from release in the UK. Chainsaw, along with The Exorcist (1975), and the original Evil Dead (1981) were probably the most high-profile targets, and the movie didn’t receive a full release on home video until the late 1990s.

Hooper quickly followed up Chainsaw with the decidedly similar hillbilly horror feature Eaten Alive/Death Trap (1977) – a forgotten gem of the era, with a serial killer who feeds his victims to his pet crocodile, and an early performance from future Freddy Krugger himself, Robert Englund – before Salem’s Lot (1979) fell into his lap.

Hooper quickly followed up Chainsaw with the decidedly similar hillbilly horror feature Eaten Alive/Death Trap (1977) – a forgotten gem of the era, with a serial killer who feeds his victims to his pet crocodile, and an early performance from future Freddy Krugger himself, Robert Englund – before Salem’s Lot (1979) fell into his lap.

Stephen King’s best-selling smash told the story of a novelist, drawn back to his home-town to write a story based on a house with a terrible and sordid history – a history about which he has been obsessed with since his childhood. Unbeknownst to him, the town has been infiltrated by an ancient evil that is slowly-but-surely spreading a vampire plague throughout the town’s inhabitants. A film adaption was originally planned, but due to the producer’s commitment to be faithful to the content and length of the original novella, it quickly transformed into a television mini-series. Produced on a budget that was one of the largest in 1970s US TV, Hooper was given the project on the strength of Chainsaw – and he certainly delivered.

The combination of the tight and punchy direction of Hooper, the excellent performances and star-power of the likes of David Soul and James Mason, and the sense of creepiness and tension that comes with introducing horror into recognisable small-town suburbia – these all contributed to making the project a big success during its original TV run, and in various re-runs over the years. The hideous image of the Barlow vampire has become iconic over the years, influencing the portrayal of vampires in various movies, games and TV shows.

The biggest project of Hooper’s career followed a few years later, when he was personally chosen by Stephen Spielberg to helm Poltergeist (1982), a supernatural horror drama that had been a pet project of Spielberg’s. Originally envisaged as a movie that he would write, produce and direct concurrently alongside ET: The Extra Terrestrial (1982), a clause in Spielberg’s contract for ET banned him from directing another movie until ET was completed. Spielberg, a big fan of both Chainsaw and Salem’s Lot, reached out to Hooper and convinced him to jump on-board.

A simple tale of an average middle class family whose idyllic suburban existence is threatened by a malevolent ghostly force, it contained plenty of the charm contained in a ‘Spielberg’ movie (especially the touching performances of JoBeth Williams and Craig T. Nelson as the parents, and the almost angelic Heather O’Rourke as the youngest daughter and focus of the spirit’s evil attention), but mixed with some of the chilling touches that Hooper had honed in Salem’s Lot.

Released theatrically a week before ET, the film was a box-office success and remained in cinemas throughout the Summer – owing in some part to the blockbuster smash that ET became (having Spielberg’s name attached, and prominently featuring child actors in the same way as ET did, certainly helped to keep the film in the public consciousness). Hooper’s direction was praised by critics and viewers, as was the innovative special effects that he employed – although there was subsequent controversy over how much involvement Spielberg had in the direction, with accusations that he overruled Hooper on a many occasions. The movie spawned a franchise of sequels that Hooper had no involvement with.

The success of Poltergeist, and a resurgent interest in Chainsaw during the mid-80s slasher movie boom, led to a proposal from infamous independent movie studio Canon Films for Hooper to develop a sequel to Chainsaw, in return for a three picture deal (with decent budgets). From that deal came Lifeforce (1985), a frankly barmy sci-fi horror movie based on best-selling novel ‘The Space Vampires’ – which as the name suggests, featured a host of extra-terrestrial humanoid vampires who run amok on earth, feeding on their victims who then return as zombie-like vampire-plague carriers. The film is a so-bad-it’s-good classic, with fantastic visual effects and bombastic performances from Patrick Stewart and (future X-Files alumni) Steve Railsback.

This was quickly followed by Invaders From Mars (1986), a relatively bland remake of the original 1950s creature-feature classic – which suffered from a woeful script, and having an obnoxiously over-the-top child actor as its lead. Even the talents of make-up effects wizard Stan Winston couldn’t save the movie from being a box-office bomb (even though his work was as awesome as always), and so Hooper licked his wounds and began work on his promised Chainsaw sequel.

Released in the summer of 1986 to great fanfare, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was a totally different beast to the minimalist, black-as-pitch original. Hooper had promised that he wouldn’t repeat himself, and wanted to introduce a little more fun to the piece, while not having to suffer the budgetary limitations of the original. Whereas the original relied purely on tension to instil horror in the viewer, Chainsaw 2 wanted to disgust the audience – with an plethora of insane gore make-up effects curtesy of the ‘gore master’ Tom Savini.

In many ways Chainsaw 2 was more of a black comedy than a standard horror movie – the actions of the Sawyer family intending to inspire just as many laughs as screams – but it was still an uncomfortable watch, even for a horror purist. The face cutting, chainsaw disembowelling, and gory torture that was just suggested in the original was there again, only this time it was accompanied by an absolute tidal-wave of blood and guts.

While Hooper was trying to make something innovative and a pastiche of the typical ‘horror movie’, Canon Films were not happy. Hooper was pressured to trim some of the more extreme and cartoony gore from the movie, and to insert more stereotypical jump scares. While still happy with the movie even after the studio-enforced cuts, Hooper did not re-sign with Canon after the end of his 3 movie deal (Canon later went bust after the disastrous box-office duds Superman 4 and Masters of the Universe). The film did relatively well at the box office despite mediocre reviews, and became a cult favourite with horror and gore fans in the years following.

While his later output amounted to a string of poorly received horror b-movies, such as The Mangler (1995 – another Stephen King adaption, this time about a possessed killer steam cleaner, I kid you not!), and Body Bags (1993 – an entertaining horror anthology movie, featuring portmanteau stories directed by Hooper and close friend John Carpenter) – Hooper achieved a bit of a renaissance in the mid-2000s. Firstly came his remake of The Toolbox Murders (2004), in which he followed the Chainsaw 2 template of turning a stark and harsh original into an almost cartoonish gore-filled feature to great results. The film has been a guilty pleasure of mine for years, and is certainly a gem in the sea of terrible horror movie remakes. This was followed by various contributions to the Masters of Horror TV series, alongside such fellow horror luminaries as Carpenter, Dario Argento, Stuart Gordon, and Takashi Miike. His episode ‘Dance of the Dead’, based on a short story from acclaimed author Richard Matheson, was generally seen as a big highlight of the entire series.

Tobe Hooper was always an individual and a man of integrity when it came to his craft. He fought his demons, but never let them dilute the quality of his output. He was known as a warm-hearted and open man, always willing to interact with the fans that so respected him. I myself am gutted that I did not get to meet him recently when he made an appearance at LFCC (his line was absolutely massive!). He will be sorely missed by the horror community.

May your saw run clean and loudly, Sir!